This weekend, someone told me their story of a recent stalking, and technically assault, encounter on the street. I was also asked how I would recommend handling the situation differently. We’ll call the parties involved, June and Betty.

June and Betty, two ladies in their 60s, were walking on a college campus, and a large man, 6’5” and 275 pounds, walked toward them. He passed them and said something crude, and they began walking away faster. He started following them, describing how he had planned for their encounter to end. Betty split up with June,, and the pursuer continued following June until he was talking over her shoulder as she tried to get away. Betty returned with law enforcement, and the man ran away. He was caught and arrested, had a prior record, including assault, and already had a warrant out for his arrest. He is now in prison.

After the incident, June’s husband encouraged her to get a pistol and her concealed carry permit, which she did. However, she said she still has not had enough training to feel like she could effectively use the weapon in a situation like this.

Before I get into what could have been done differently, I want to say it is easy to Monday Morning Quarterback a situation when you were not there, aren’t really aware of all the details, and don’t have the stress and emotion that come from being in the situation. So, when a person successfully gets through a situation like this, I say, “Good for them; they made the right decisions.”

However, we can all still learn from someone else’s experience. At the first verbal contact, if there is no clear place of safety or a group of people nearby, they could have faced the perpetrator and established a verbal boundary. The verbal component takes practice.

“Stop right there, I can hear you fine from right there.” This establishes a verbal boundary, but you must be prepared for a physical follow-up if they ignore you or feign compliance. If you have any defensive tool, now is the time you should be introducing it if you have not already.

The verbal boundary does a couple of things. First, it shows the perpetrator that you are willing to stand up for yourself and communicates that you are more likely to fight back. Second, it is a pattern disruption for the aggressor, meaning they are potentially reacting to you. Finally, it is a component in determining if the person is all talk and willing to walk away, or if the person is more dangerous. It is better to learn this with as much distance as possible. Distance equals more opportunity for action on your part.

“Can you stop right there? I can hear you fine.” This is the type of verbal boundary I see a lot of people default to in our workshops. It is better to make a statement than to ask a question. When you ask a question such as, “Can you stop right there?” you are almost inviting him to say “no” verbally or physically.

“It may have looked that away. If it did, I didn’t mean it. But I need you to stop right there.” A more advanced verbal technique involves acknowledging their concern without agreeing with them. This really takes a lot of practice. In our ongoing self-defense classes, students have several months of training before advancing their verbal skills to this point.

“You’re right. I messed up. Can you stop right there?” I see a lot of people default to apologies in our workshops. There is a chance that agreeing with the aggressor may deescalate the situation, but it may also make them feel you have justified their actions. They may feel that since you acknowledged that you were wrong, you must have done it on purpose, or your actions are seen as submissive.

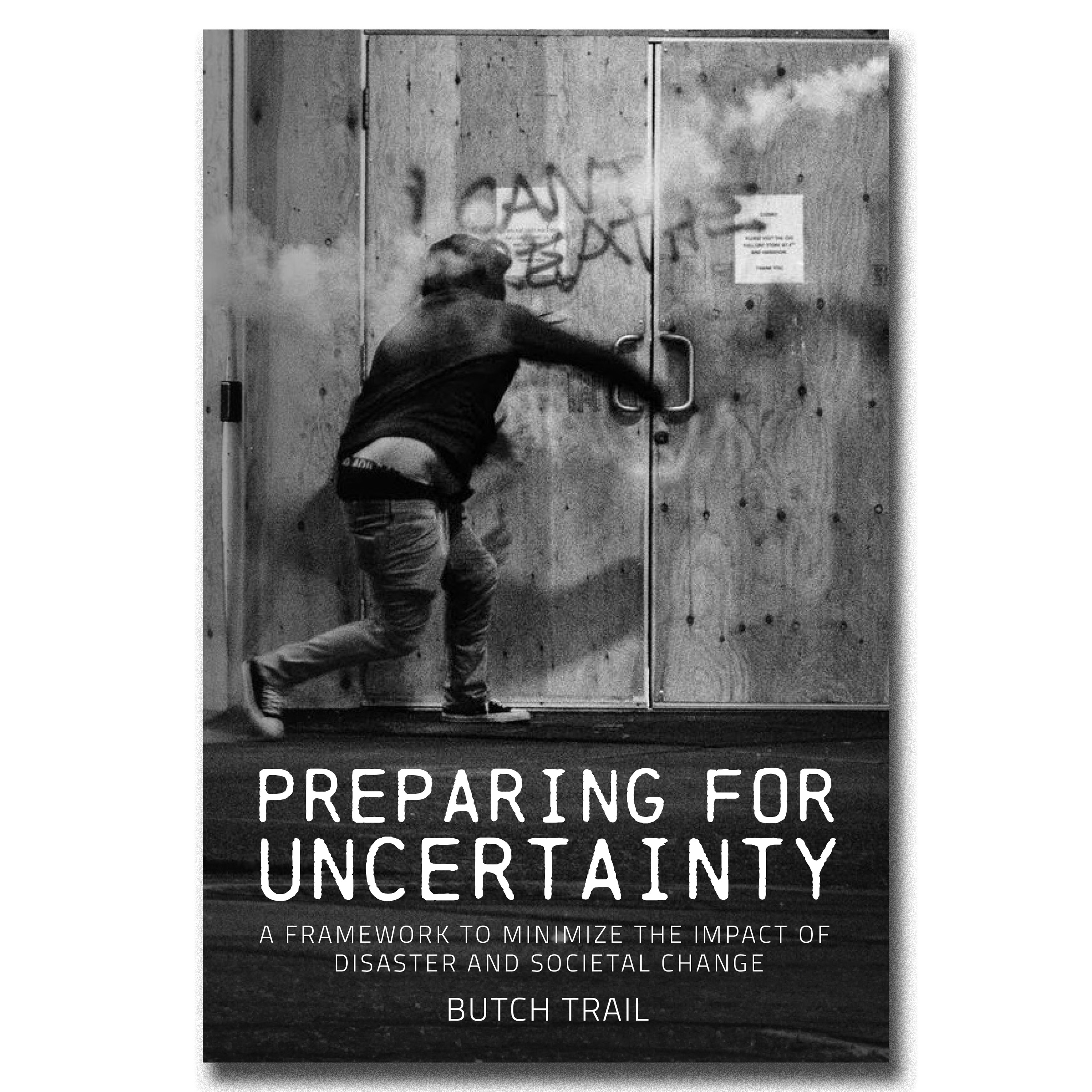

All the verbal boundary settings need to be followed up with the ability to initiate a physical response if they pursue you. The overall strategy and more details are covered in Preparing for Uncertainty. But in the meantime, work on finding a statement that is authentic to the way you talk in order to establish that first verbal boundary.